Research

At this point in the process, my immediate goals were two-fold.

The pipeline I arrived at in terms of incorporating research into creature design was primarily the product of combining the workflow of two creatures artists with vastly different, but well documented approaches to creature design. The first is Terryl Whitlatch, whose trilogy of books of creature design serves at the key text of biologically-based creature design. However, Whitlatch’s process is entirely geared towards traditional media, which is why is is counterbalanced in my work by also drawing from creature concept artist R.J. Palmer. While a relatively new face in the concept art works, he excels at rapidly prototyping digital creature designs to high degrees of polish with a systematic, almost mathematical approach. Meshing these two processes gives a pipeline that can be expressed in this rather intimidating list.

In broad strokes, the concepting of the creature is very much Whitlatch, and the execution is very much Palmer.

Ideally, this process gives me a cyclical pipeline where each creature influences the creature that descends from it in a an organic, yet informed way.

The pipeline, in turn, informs the deliverables of the project. In order to pitch this idea before I had creatures to present, I used a placeholder creature to express my plans. That creature was the 'murp'.

- Develop a pipeline for the project to follow.

- Learn everything I could about the time period and animals involved.

The pipeline I arrived at in terms of incorporating research into creature design was primarily the product of combining the workflow of two creatures artists with vastly different, but well documented approaches to creature design. The first is Terryl Whitlatch, whose trilogy of books of creature design serves at the key text of biologically-based creature design. However, Whitlatch’s process is entirely geared towards traditional media, which is why is is counterbalanced in my work by also drawing from creature concept artist R.J. Palmer. While a relatively new face in the concept art works, he excels at rapidly prototyping digital creature designs to high degrees of polish with a systematic, almost mathematical approach. Meshing these two processes gives a pipeline that can be expressed in this rather intimidating list.

- Research into real world evolutionary research.

- 1.1.Paleontology

- 1.2.Biology

- 1.3.Paleobotany

- 1.4.Anatomy

- 1.5.Archeology

- 1.6.Sociology

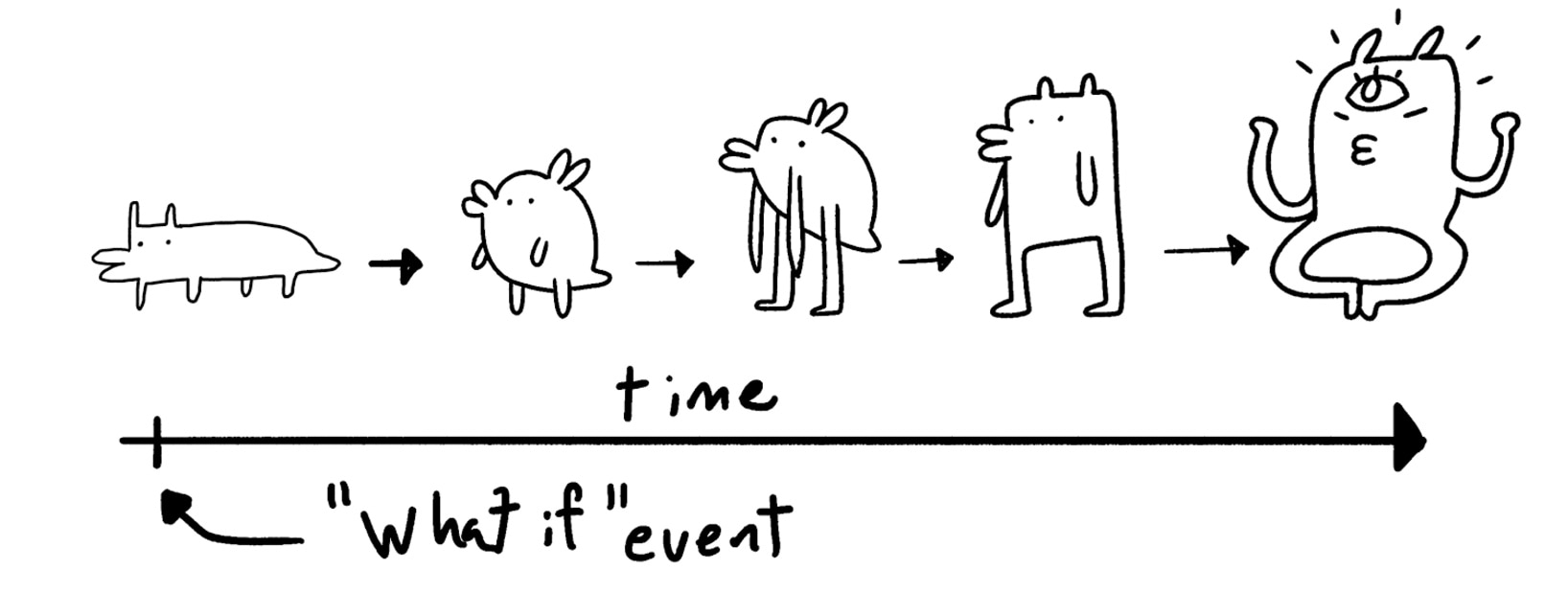

- Identify a point for divergence: Finding a point in time where things could have gone differently, the split in the evolutionary path where a small difference could ‘butterfly effect’ the timeline.

- Formulate a ‘what if’ question that defines the hypothesis of the world-building exercise. (i.e. What if the dinosaurs hadn’t died out.)

- Creature conceptualizing

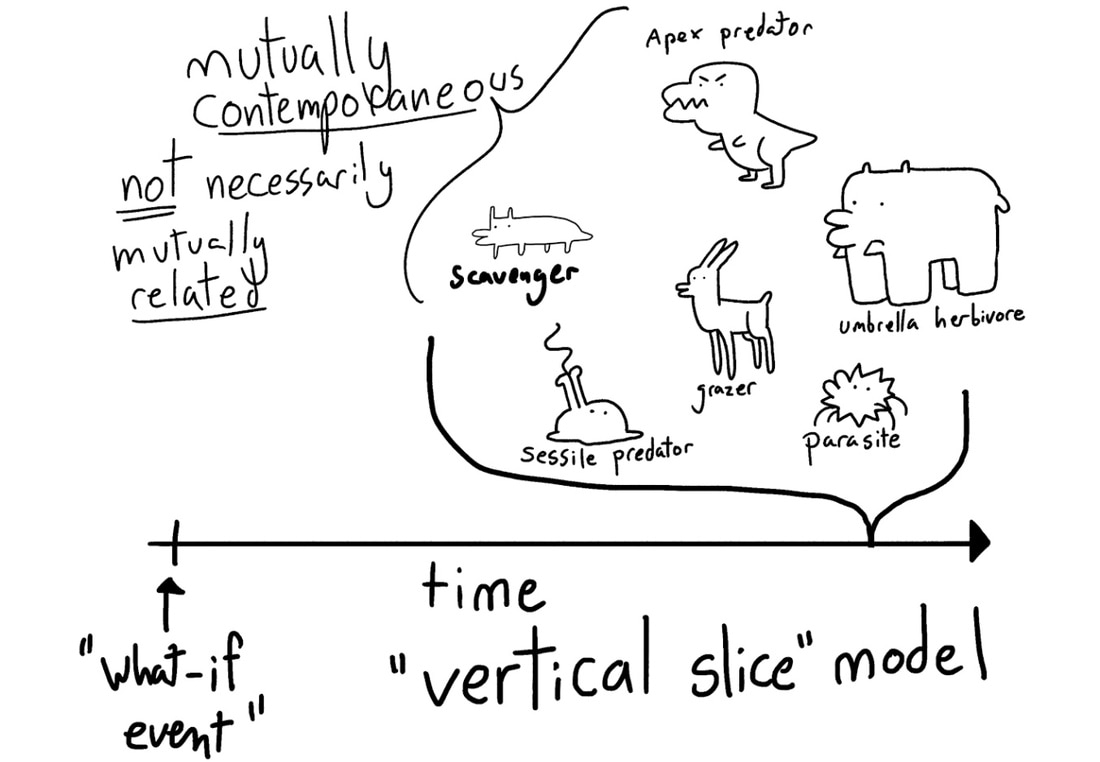

- 4.1.Identify vacant evolutionary niches: Because of the recurring patterns in evolutionary history, certain evolutionary niches are inherent to an ecosystem, i.e. apex predators, scavengers.

- 4.2.Evaluate biological resources available. Up until the point of divergence, what do we know about the life that is available to have filled those niches? this is largely dictated by the hypothetical environment, involving paleogeography and paleobotany.

- 4.3.Speculate resulting impact upon the ecosystem of proposed creature.

- 4.4.Repeat steps 4.1 through 4.3 as needed to generate creature concepts.

- Speculate anatomical support for primary adaptations, e.g. If the creature’s main method of defense is huge horns, how does its body support that feature?

- 5.1.Compare to extant life: Speculative evolution requires that living bodies follow the same rules as extant creatures, so we can look at the real-world to answer questions about the hypothetical animals.

- 5.1.1.Intense study of extant animal physiology and anatomy.

- 5.1.Compare to extant life: Speculative evolution requires that living bodies follow the same rules as extant creatures, so we can look at the real-world to answer questions about the hypothetical animals.

- Creature design

- 6.1.Conceptualizing with chimeras: Creatures can be roughed out by mashing incompatible animal anatomy. e.g. a centaur

- 6.2.Design genetic blend: Incompatible anatomy is made compatible in such a way as to avoid being a chimera. e.g. A labradoodle as opposed to a labrador with the head of a poodle.

- 6.3.Anatomical illustration: Creature is rendered in orthographic view. Anatomical levels on different layers.

- 6.3.1.Skeletal system.

- 6.3.2.Muscular system.

- 6.3.3.Skin layer.

- 6.3.3.1.Fur/feathers/display or camouflage markings.

- Behavioral impact

- 7.1.How does the creature’s physiology impact its behavior? Can it be compared to an extant animal? What is its relation with other lifeforms in its ecosystem?

- 7.2.If sentient, explore cultural development of creature.

- 7.2.1.Social structure.

- 7.2.2.technology

- 7.2.2.1.Costumes

- 7.2.2.2.Props

- 7.2.2.3.Architecture

- Scene design: creating a tableau depicting creatures as they might appear in life.

- 8.1.Layout of scene with thumbnails

- 8.2.Illustration

- Accompanying text informed by research

- 9.1.Scientific names

- 9.2.Mimic field guide style

- graphic design/layout

- Publication

In broad strokes, the concepting of the creature is very much Whitlatch, and the execution is very much Palmer.

Ideally, this process gives me a cyclical pipeline where each creature influences the creature that descends from it in a an organic, yet informed way.

The pipeline, in turn, informs the deliverables of the project. In order to pitch this idea before I had creatures to present, I used a placeholder creature to express my plans. That creature was the 'murp'.

|

The murp allowed me to design both the selection process for the creatures we would be looking at, as well as block out the website you're reading right now. The options I considered at the time were:

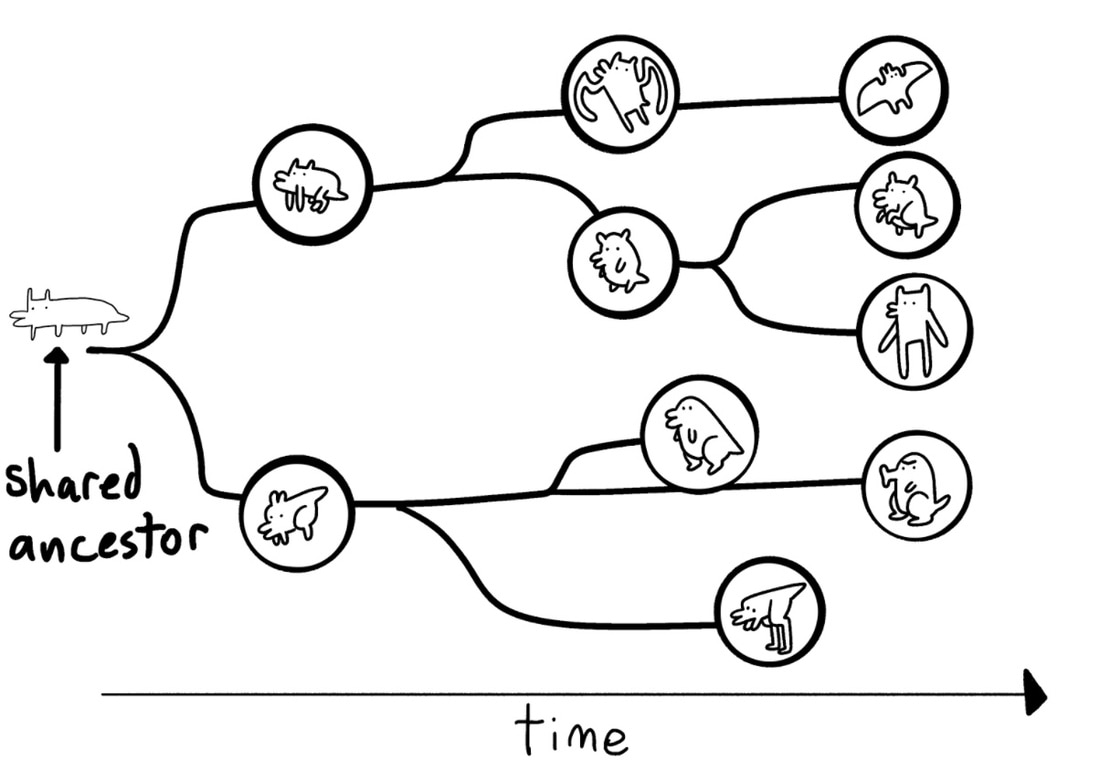

The 'Lineage' model A straightforward progression of descendence from the oldest ancestor to the newest descendant. The 'Vertical Slice' model The creatures we look at exist contemporaneously, removed from the time of the What-If event my millions of years. Dougal Dixon is fond of this model. The 'Family Tree' model We take a single, exsitent creature, and follow their branching descendance through time, seeing how the same base genetic stock reacts to evolutionary pressures and time in radically different ways. |

Though it was the most ambitious in scope, I ended up going with the family tree model, because I believed it could be represent the principles I believed I could put into practice.

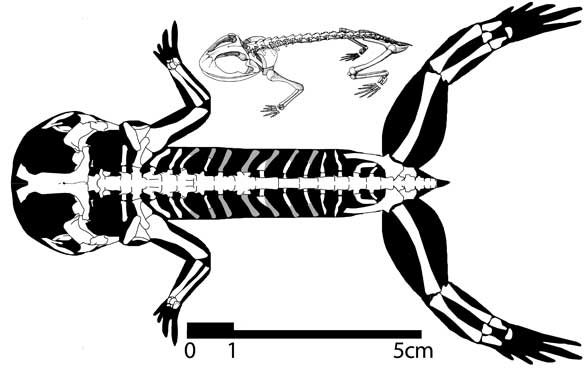

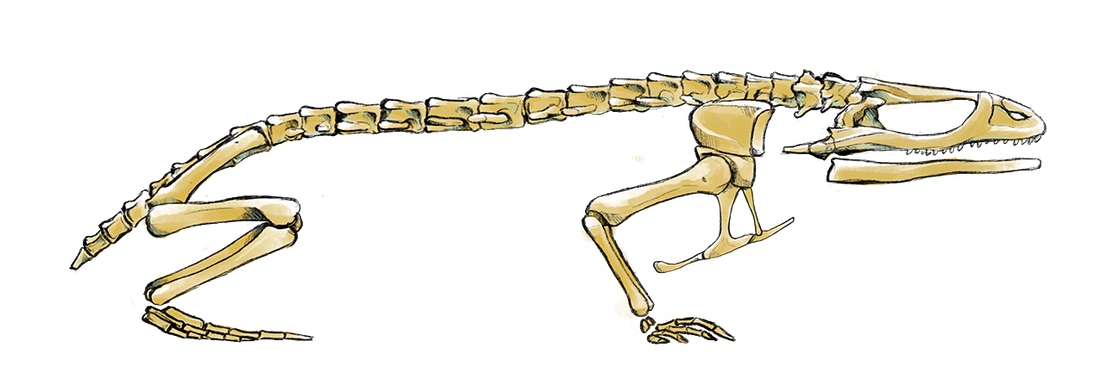

Time finally came to find my base creature, a creature that did exist at the time of my 'What-If' question. Our event in question, regarding the relative humidity of the world 252 million years ago, takes place right on the boundary between the Permian and Triassic, so it is commonly known as the P-T event. The dryness of the moment led to reptile dominance, so naturally, I chose to explore the possibility of amphibian dominance. Amphibians would thrive in a more humid, moist P-T event, and, indeed, until far into the development process of the thesis, I referred to the Amphiterra Project as ‘MOISTWORLD’. I still prefer the old name, but it just didn’t test well. Looking at the creatures of the time, I found my candidate: Triadobatrachus massinoti, commonly acknowledged as the most recent common ancestor of both frogs and salamanders. I liked the idea of huge, grandiose creatures coming from something so delicate and small. And, yes, at the end of the day, I just really like frogs. In attempting to research and reconstruct Triadobatrachus, I would be experience firsthand whether my proposed pipeline would work.

Time finally came to find my base creature, a creature that did exist at the time of my 'What-If' question. Our event in question, regarding the relative humidity of the world 252 million years ago, takes place right on the boundary between the Permian and Triassic, so it is commonly known as the P-T event. The dryness of the moment led to reptile dominance, so naturally, I chose to explore the possibility of amphibian dominance. Amphibians would thrive in a more humid, moist P-T event, and, indeed, until far into the development process of the thesis, I referred to the Amphiterra Project as ‘MOISTWORLD’. I still prefer the old name, but it just didn’t test well. Looking at the creatures of the time, I found my candidate: Triadobatrachus massinoti, commonly acknowledged as the most recent common ancestor of both frogs and salamanders. I liked the idea of huge, grandiose creatures coming from something so delicate and small. And, yes, at the end of the day, I just really like frogs. In attempting to research and reconstruct Triadobatrachus, I would be experience firsthand whether my proposed pipeline would work.

|

Triadobatrachus presents an interesting series of challenges in that the specimens available are incomplete. Our information on its snout, front and back feet has to be derived from comparative anatomy against other fossil specimens and extant animals.

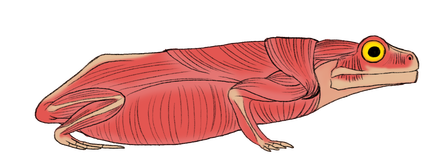

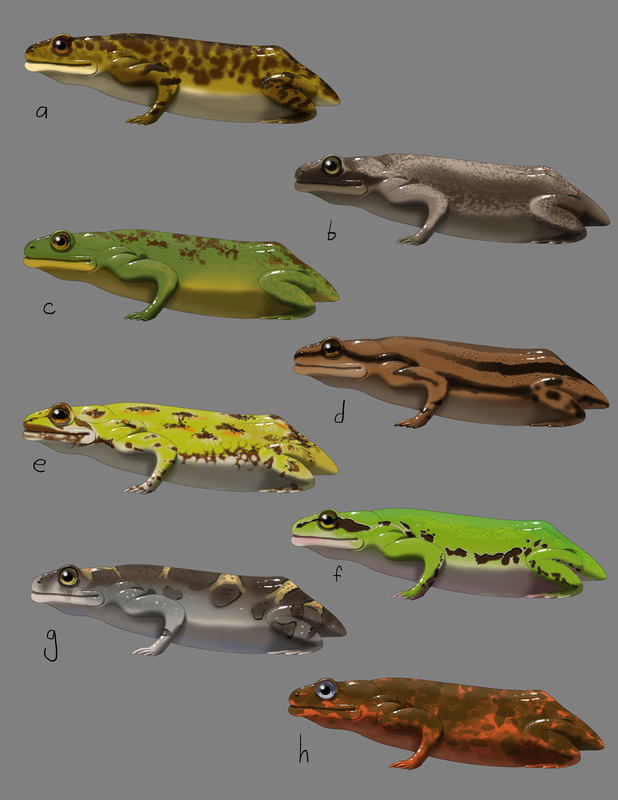

In terms of direct anatomical comparison, my main sources were the Hula painted frog, a 'living fossil' with notoriously primitive anatomy, Gerobatrachus, a near descendant of Triadobatrachus, and the American bullfrog. It was at this stage that I realized there is a very real dearth of skeletal reference for amphibians from any angle other than a top-view. Though I explored some digital options, I couldn't find the level of detail I wanted. In the end, I bought a mounted American bullfrog skeleton off Amazon, which did end up giving me the reference I felt was necessary for the side-orthographic views I cribbed from Whitlatch's process. Based on these sources, I produced a skeletal model which filled in the gaps left in the fossil record for our creature. From there, I looked for the points of integument on the skeleton and based a muscular system off of that, using modern frogs as a guide. I found that starting at the eyes made the process much simpler, and keeping in mind the places where muscles overlap. It was at this point I noticed something that would prove to be a tremendous sticking point for all of my creatures: amphibians don't have ribcages, instead incorporating thick, muscular rings to protect their internal organs, giving them their characteristic squat silhouette. Each Amphiterran creature is designed with this feature in mind. Using the hula frog's exterior anatomy as a basis, I designed a skin-level drawing for the creature, and then put it through an iterative process of color selection using inspiration from extant frogs living in similar environments. The color scheme I chose is meant to incorporate features of camouflage as well as a pattern which could break up the creature's silhouette, confusing a predator. From this point, we now go into the technical process of rendering a high detail creature in DESIGN. |