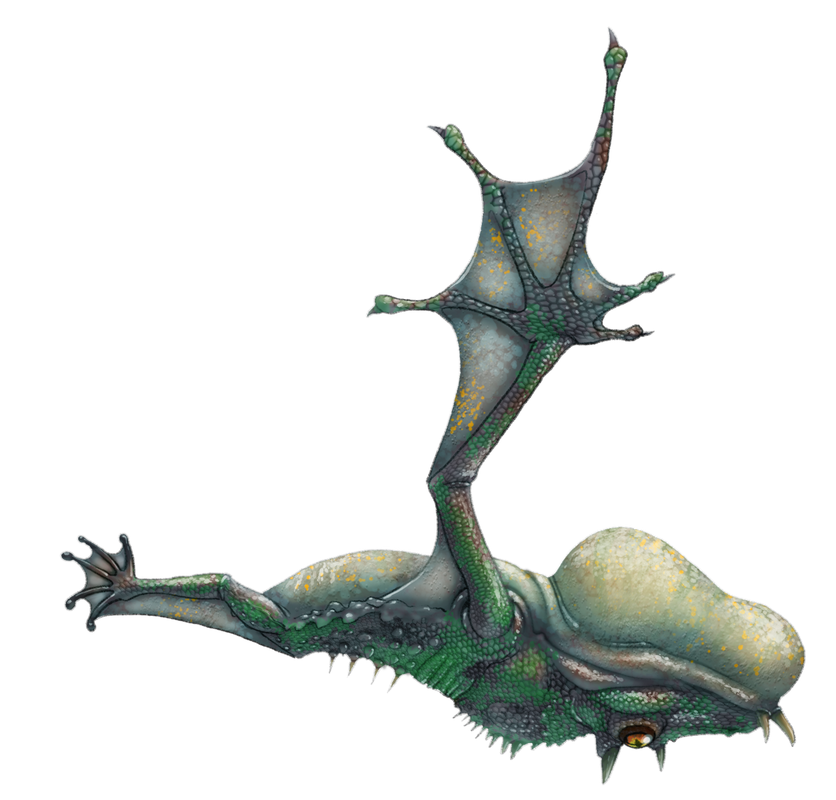

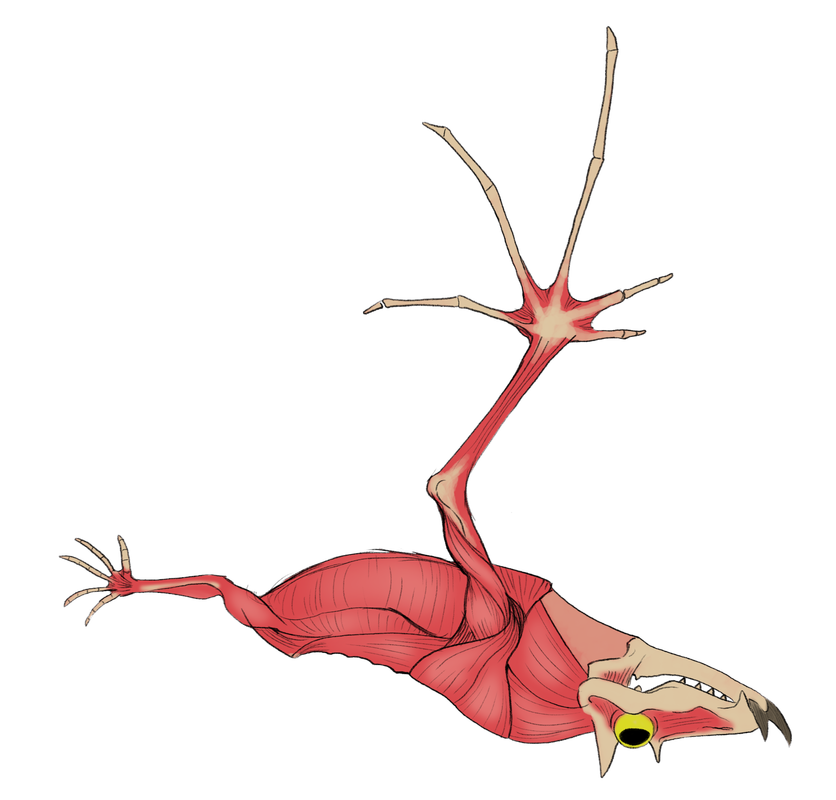

fig A: The gliding alloo waits, perfectly camouflaged against a mossy tree, its crocodile-like eyes able to observe everything around it without sacrifing its camoflage.

fig B: The gliding alloo peels off from its perch and silently glides towards its prey.

fig C: The alloo pins its prey with its venomous dorsal spines.

|

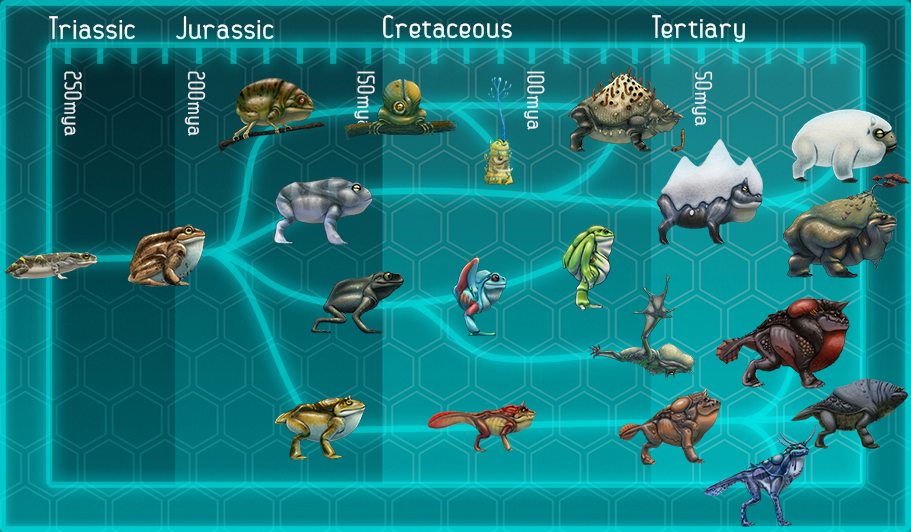

Amphibians never truly mastered the air thus far in the Amphiterran timeline. The rigours of self-powered flight are simply not compatible with ectothermic, low metabolism amphibians. The air is mostly dominated by huge insects and the descendants of our own lineage, bat-like quasi-mammals occupying the niche of birds. However, a pioneer into the heights in the Amphiterran timeline is the unconventional gliding alloo.

The gliding alloo lives amongst the redwood-tall fungal forests, and feeds on the myriad small vertebrated that live on its various levels. To hunt, the alloo will climb a tree using it strong, thorny grip to haul itself up. The alloo’s eyes are rotated almost to back of its head, so it has a perfect view of what’s happening behind it while it climbs, and gives it binocular vision to calculate the distance to its prey. With the target in sight, the alloo leaps backwards, falling back-first towards the forest floor, were it not for the specialized membranes between its toes, which it uses to control its descent, and the unique gular sac, which inflates to cause drag. The inflated sac creates no lift, but rather acts like a parachute made out of a balloon, slowing the alloo’s descent just enough to let it control its trajectory and land on its prey, pinning it under its body and devouring it. As bizarre as the alloo’s stratagem might seem, it is not unlike the early stages of animals in our timeline which achieved flight, such as Archeopteryx leading to modern birds. The future may yet hold skies dominated by the alloo’s curiously inverted descendants. |

EVOLVES FROM: